Tempura, a staple food found throughout Japan, surprisingly has its origins in Portugal and was introduced to Japan during the Muromachi period (1300s) by Portuguese traders or missionaries. The name is said to come from the Latin word tempora, referring to fasting periods when people refrained from eating meat and instead consumed fried vegetables or seafood. The original Portuguese version used a thick batter, quite different from today’s light and crispy tempura. However, due to the scarcity of oil as a luxury item during that era, tempura was not readily available to the general public and was enjoyed only on special occasions.

Following the Taisho period (1926), tempura evolved into the style we recognize today, featuring a light and crispy batter served with a dipping sauce. The modernization of food culture, along with the spread of restaurants specializing in fried dishes, helped establish tempura as a distinct category of Japanese cuisine. After World War II, the increased availability of oils and household ingredients made tempura a common dish in Japanese households, and it gradually became a comfort food enjoyed across all generations.

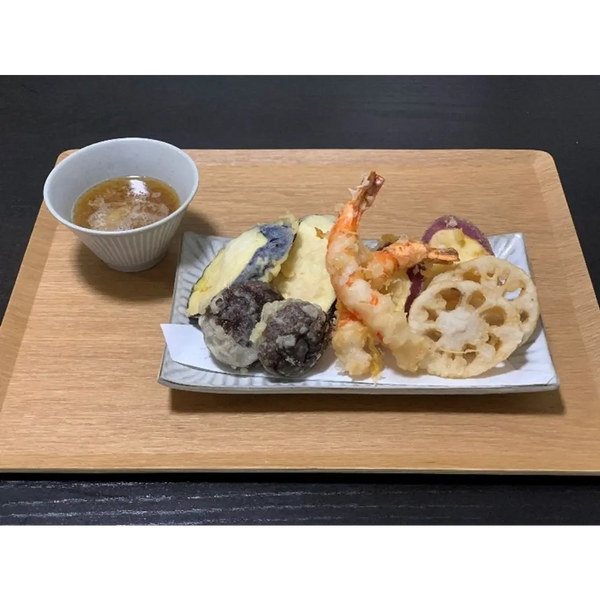

Tempura can be enjoyed as a main dish at home or in tempura restaurants, as well as in combination meals with soba noodles or served over rice as tendon, drizzled with a sweet sauce. It is also a popular choice for bento boxes and festive meals, thanks to its versatility and the wide variety of ingredients that can be used, such as shrimp, fish, root vegetables, mushrooms, and seasonal produce. Tempura fillings have no strict rules—seafood and vegetables are the most common, while meat is rare but may appear in certain regional specialties. The ingredients introduced in this recipe represent those most commonly enjoyed in everyday Japanese households.

The differences between Kanto and Kansai style tempura are notable and reflect deeper regional food cultures. In Kanto, a batter made from wheat flour, eggs, and water is used, and tempura is deep-fried quickly at a high temperature using sesame oil, resulting in a fragrant and slightly richer flavor. In Kansai, however, only wheat flour and water are used in the batter, and tempura is deep-fried slowly at a lower temperature using salad oil (known as vegetable oil in other countries), creating a lighter and more delicate finish.

The choice of oil and frying methods reflects regional preferences. In Kanto, where fish is commonly used, sesame oil helps to remove fishy smells and enhances the umami of seafood. In Kansai, where vegetables are popular, salad oil is preferred because it allows the natural sweetness and freshness of the vegetables to shine.

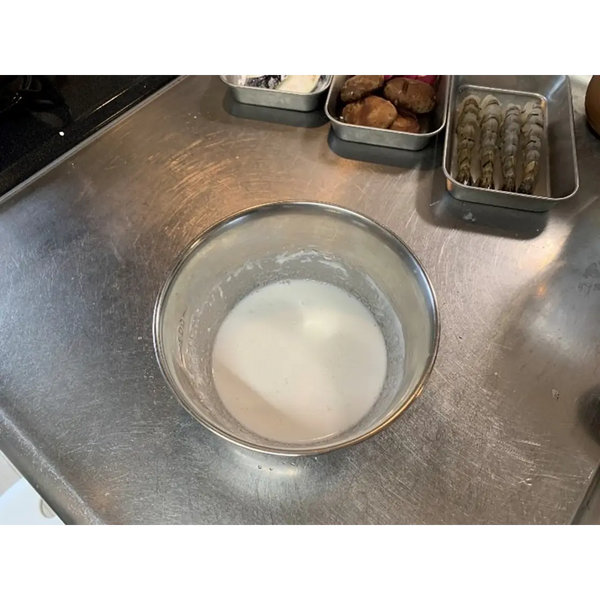

Today, we’ll introduce a Kansai-style tempura recipe made gluten-free using rice flour, ensuring everyone can enjoy this dish at home. Tempura made with rice flour also results in a crispier texture that stays crunchy for longer, making it a great option for beginners and experienced cooks alike.

In Japan, tempura is typically enjoyed with Mentsuyu (concentrated Japanese soup base) and grated daikon radish, or simply with salt. Some regions also serve it with matcha salt or yuzu salt for an aromatic twist. When dining out, many restaurants offer not only classic items but also seasonal specialties such as oysters in autumn or nanohana (rape blossoms) in spring—served at their peak with the simplest preparation to highlight their natural flavor. Don’t hesitate to ask the staff about their recommendations or seasonal offerings; it’s one of the best ways to enjoy tempura at its finest.